Beyond Laughter

When I was at university, I was convinced that translation was my passion. Actually it was, until I stepped into the real world of translation for the first time. I was 21 years old, freshly graduated, and so excited about the thought of beginning a new journey. I still remember my first day at work: within a single hour, I swung from happiness to disappointment. And from that moment on, the hours grew longer, the work heavier, and I found myself suffocating beneath it all. I needed something, anything, to pull me back to life and to fill the silence of long hours spent behind the screen. That’s when I discovered the plays of Ziad Rahbani.

Of all his works, “Bennesbeh Labokra Chou?” (What About Tomorrow?) became my favourite. When I first listened to it, I was particularly impressed by Ziad’s style and sarcasm. Taking place in the 70s, this play, a famous humorous comedy with catchphrases that are widely used in daily Lebanese life, is the story of Zakaria and Suraya a couple working in “Sandy Snack”, a bar in downtown Beirut and their daily struggles to make a living for their children. From a village to the city, Zakaria and Suraya are doing their best to get out of poverty. However, serving clients in a bar is not enough to make a decent living, so Suraya finds herself going out with the bar’s foreign clients in return for extra money. Zakaria who tries to be ok with this all along, ends up stabbing one of those clients and is thrown in jail. Ironically, things go back to normal two weeks later.

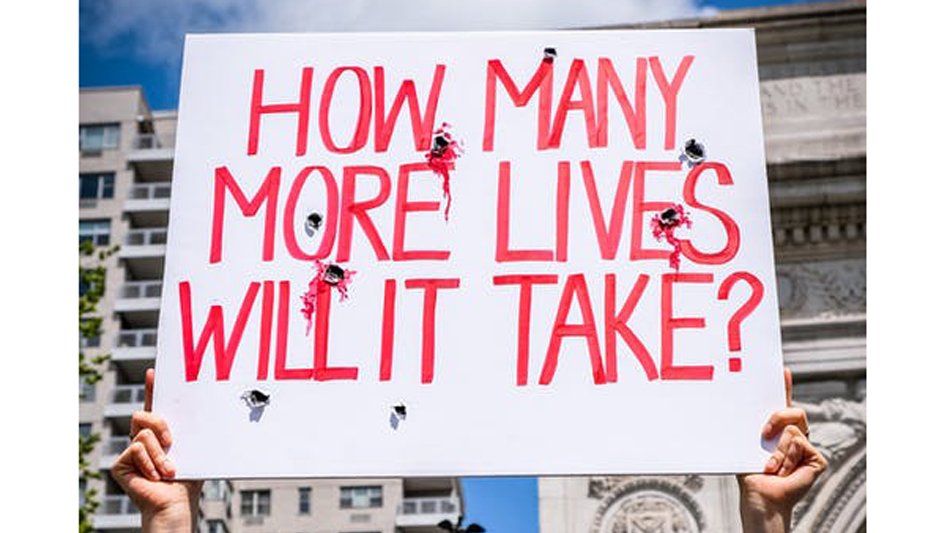

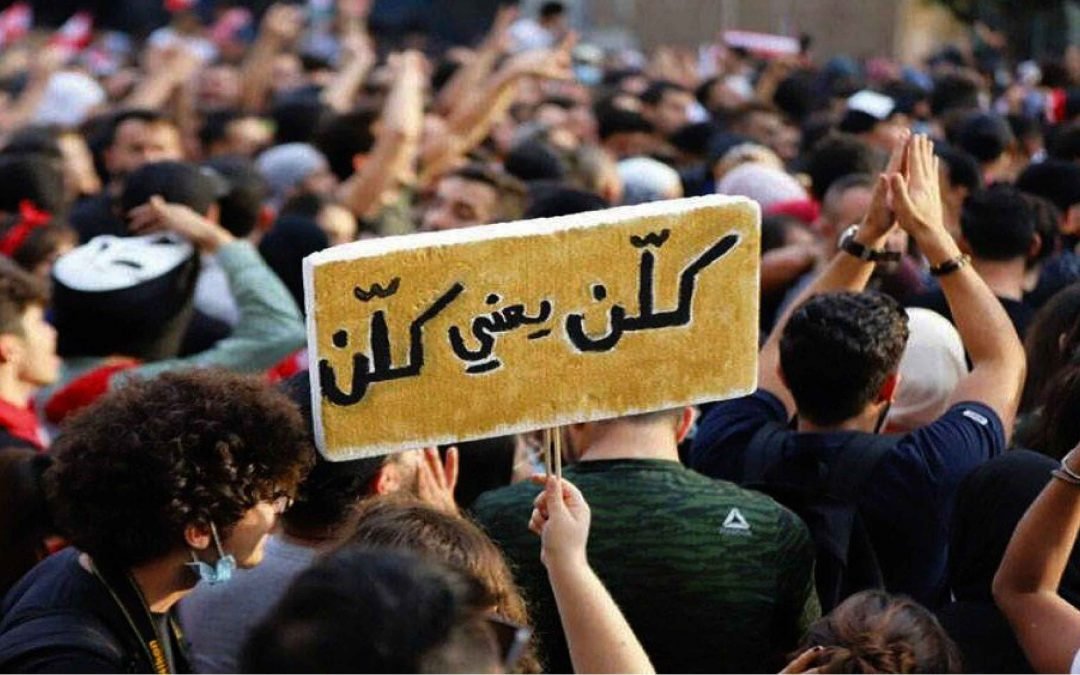

Source: 7iber.com

“Bennesbeh Labokra Chou” draws a true picture of the Lebanese society at the time, and at any time in fact. It is a society filled with humor, contradictions, and underlying tensions. Each character reflects a different aspect of the country’s struggles, and together they bring to life a story that is both entertaining and deeply symbolic. Zakariya is that Lebanese who is aspiring for a better life. He has values, but at the same time, he is ok with jeopardizing those values to improve his life conditions. He holds clean hands while others get dirty with his permission and under his blind eye. Unfortunately, with every taste of luxury, he becomes unwilling to give it up and drowns into moral decay, but since he is a person rooted in ethics, there comes a day when he finds out that he doesn’t want to sell his soul for anything anymore. At that moment, something in him breaks and violence takes over.

His wife, Suraya is that Lebanese who is willing to sacrifice standards to build a house on broken values that she calls stability. When others point out the wrong she is doing, she is ready to justify it and to play the victim who is unhappy with her situation, but forced into her actions. To her, it’s life that has been unfair.

In addition to Zakariya and Suraya, two interesting characters, the owner and the manager of the bar are drawn into progress and financial gains despite the calamities. As Zakariya is thrown in jail and Suraya falls into depression, the manager tells her “A disaster has occurred, it’s ok. You have to bear it”. After all, life must go on and people must live with all the disasters that have struck their country since the dawn of time. This reminds me of a popular Lebanese song that we grew up hearing; it says “the country’s working, work is moving, people keep talking, so don’t worry about anything”.

Beneath every joke in Ziad Rahbani’s play is a sad truth and Ziad was very good at reframing this truth no matter how difficult or painful it was. In fact, humor is reality in disguise. It often tells the truth in such a way that makes it easier to accept. The choice of the characters and everyday chaos doesn’t just make the play entertaining, but also shows how our brains react to humor that’s deeply rooted in real-life situations.

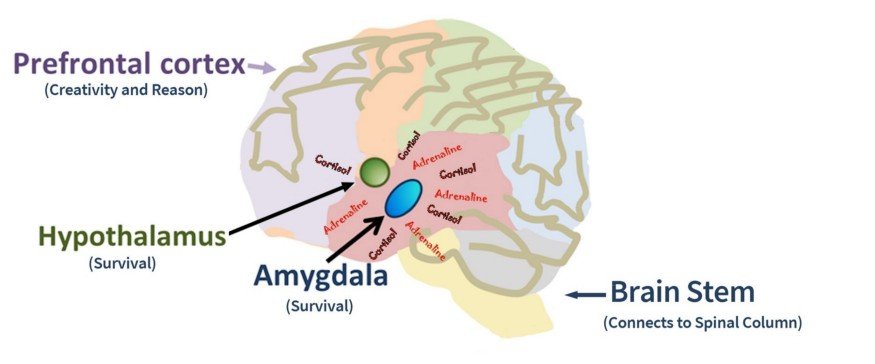

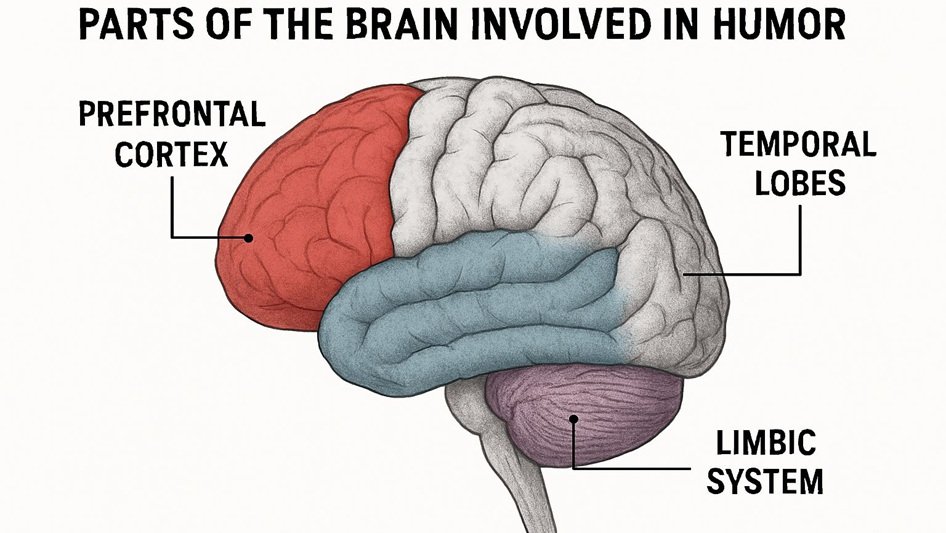

Researchers have been looking into how our brains process humor. Our brains activate multiple regions simultaneously: the prefrontal cortex, responsible for cognitive processing and decision-making; the temporal lobes, which help with language and comprehension by creating a context for humor; and even the limbic system, which is involved in the release of dopamine, the “feel-good” chemical. In other words, when we laugh, it’s not just emotional, it’s neurological. Our brains are literally rewarding us for understanding a joke, and for connecting the dots between contradiction and truth.

For me, that play wasn’t just a cultural masterpiece. It was neuroscience in action. It pulled me out of a numb, monotonous routine and reawakened parts of my mind and heart that had gone quiet. Word by word, I was learning that Ziad’s plays, all of them actually, were not just entertainment, but more like coded messages from a time when saying too much out loud was dangerous. Word by word, joke by joke, I was learning how creativity is born under the pressure of wars, as well as political and religious divisions. Word by word, joke by joke and laugh by laugh, I was learning that, most importantly, theater is a translation of reality. It is that mirror that reflects truth and empowers it. Just as translation converts a message from one language to another, theater translates emotions, stories, and cultures into performance that becomes universally understood. After all, translation, in any aspect, is a real pleasure and passion for those who find joy in words and meanings and who love bridging cultures and differences. Ziad’s humor was not attempting to escape reality, but to face it.

So next time you hear some humor, listen closely, and you will realize: the jokes are doing more than making you smile. They are telling you the truth.

For citations:

APA Style

Saad, C. (2025, September 7). Beyond Laughter. Beyond the Words. https://beyondthewords.blog/2025/09/07/beyond-laughter/

© 2025 by the author.